Federico Marri is an Italian PhD student in economics who has earned both a Bachelor of Science (2021) and a Master of Science (2023) in Economics from Bocconi University, Milan, Italy. He worked for one year as a researcher at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Federico’s research interests lie at the intersection of economic growth, political economy, and cultural evolution. His research focuses on understanding the drivers of economic growth in a long-run perspective.

In his free time, Federico enjoys playing soccer, tennis, and chess, as well as reading Greek Tragedy and Italian poetry.

Scholar Voices

Global Leadership Vision Op-Ed | Lemons, Politicians, and the Need for Courage

By Federico Marri | November 2025

When my friend entered politics at eighteen, she carried the kind of idealism every democracy dreams of: sharp mind, strong competence, genuine care for her community. She spent five years organizing events, paying campaign costs from her own pocket, and believing her party’s promise of letting her promote policies for the youth. When the election came, they turned against her—blocking her from speaking at her own rally and retracting their support. The experience left her so hurt and disenchanted that she abandoned politics altogether; today, she can hardly bring herself to read a headline.

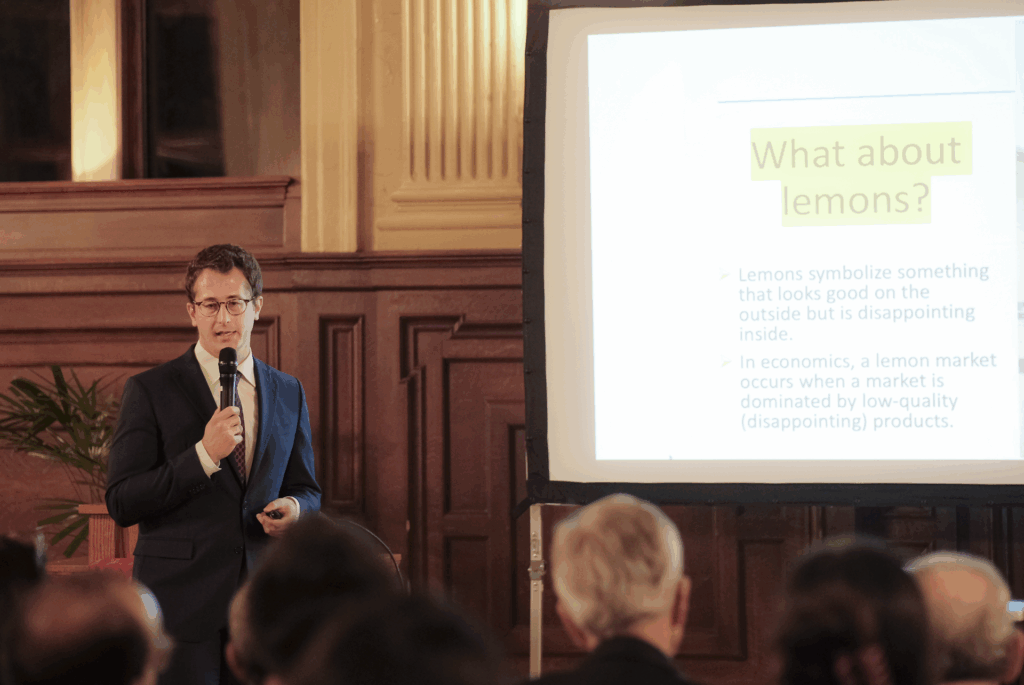

In economics, adverse selection refers to the phenomenon that occurs when one party in a transaction has more information than the other about some key characteristic and, because of this, the good products are driven out of the market. In the classic example developed by George A. Akerlof in “The Market for Lemons,” sellers know whether the car they are selling is a “peach” or a “lemon,” but the buyers don’t. Anticipating this asymmetry, buyers will only offer an average price and high‐quality car owners will withdraw from the market. As a result, only lemons (low-quality cars) will be offered.

Now consider politics. Voters are the “buyers” of representation, and politicians are the “sellers.” Citizens cannot directly observe many important attributes such as integrity, altruism, competence, or a long-term orientation toward the public good. In this setting, if high-quality politicians are unable to signal their type effectively, individuals driven by self-interest, possessing weaker moral constraints and lower competence, may find greater incentives to run. Economists Francesco Caselli and Massimo Morelli have shown under which conditions citizens of low quality—meaning less competent or less honest—have a comparative advantage in entering politics. For example, their opportunity cost of running may be lower (since their outside wages are lower or because they face smaller reputational costs). Over time, the “market” of candidates becomes dominated by lemons.

Some might object that, in a democracy, voters freely choose their representatives—so if politics seems full of “lemons,” perhaps that’s a reflection of what the public wants. Maybe voters value different qualities than the ones I’ve emphasized above. Yet survey data suggest otherwise: according to the American Bar Association, 85% of U.S. adults believe elected officials do not care what people like them think, prioritizing instead donors, lobbyists, and large employers. Likewise, among registered non-voters, the most common reasons for abstaining are “dislike of the candidates” and “no good choice.”

What can be done? Standard market solutions (screening, signaling, transparency) are difficult to apply to politics; therefore, a complementary argument for courage can be put forward.

Courage in politics means that citizens run for office even when, in expectation, the reward seems low and the equilibrium unfavorable. It takes courage for competent, ethical citizens to enter a system that, on purely utilitarian grounds, does not reward them: courage to accept reputational costs, to earn less than they could elsewhere, and to devote time, energy, and effort that could otherwise advance their already high-achieving careers. My friend’s story is not unique, but it doesn’t have to be the norm. Courage, then, is not just a personal virtue, but something that keeps democracy alive.